Welcome back to AND ANOTHER THING! Today, I’m pressing pause on the style reporting to celebrate Samuel Butler, my grandfather-in-law and a larger-than-life character I’ll always remember as a true American hero. Thanks for being here.

Both of my grandfathers died before I was born. My dad’s dad, Fred Louis Blasberg II, who kept the books for a few local businesses in South City, St. Louis, passed away in 1954, when he was 47 and my dad was only 14 years old. My mom’s dad, Frank Overman Egendoerfer, who worked as a beer bottler at the Falstaff brewery, died in 1976 at the age of 64.

“Both deaths can be attributed to cigarette use,” my mom wants me to mention, much to my annoyance. I’m 43, and I don’t smoke! “Both dads smoked Marvel cigarettes, a cheaper, unfiltered cigarette.” We get it, Mom. We get it!

Sure, I had paternal influences growing up—my father (a legit saint), as well as uncles, teachers, family friends. But when I watched movies like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, I could never relate. How would I have found the golden ticket like Charlie without a Grandpa Joe? Even The Godfather made me wistful: Where was my rotund, cotton-mouthed Marlon Brando? My morally compromised patriarch willing to bribe, lie, and extort in the name of family loyalty?

When I met Nick, my partner, he was the total package. Handsome, kind-hearted, hardworking, a terrible driver who was always impressed by my ability to parallel park a rental car on the first try. What sealed the deal for me was his family—and at the head of it, his maternal grandfather, Samuel Butler, “a living legend of the New York bar,” according to a 2007 Wall Street Journal profile, who died this year at the age of 94.

Last week, we celebrated his life at a poignant, fabulous memorial, complete with show tunes and fried pork sandwiches and a five-tier chocolate cake. It was a perfect, grand send-off for a man whose strict sense of structure was always balanced by deep (and maybe surprising) warmth and compassion. A lawyer with a heart of gold? It’s possible?

But, wait. We’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Born in 1930 in Logansport, Indiana, Sam was the valedictorian of Culver Military Academy in June 1947; went to Harvard for undergrad, where he graduated magna cum laude and lettered in football; and then graduated magna cum laude (again!) from Harvard (again!) Law School in 1954, where he was editor of the Harvard Law Review.

He wasn’t a particularly vain man, but I think he’d appreciate me mentioning he was also a stone-cold fox. Look at his old passport photos:

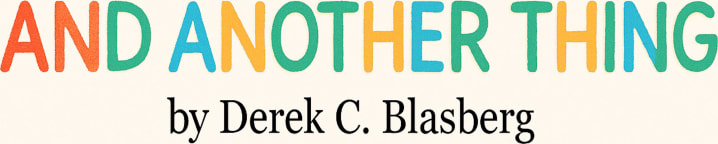

In high school, Sam met Sally Thackston at a friend’s house, fell in love, and wed on June 28, 1952, when they were both 21. They remained happily married for the next 71 years. (Sally, a dignified, elegant woman to the end, passed away at home surrounded by family in October 2023.)

Sam clerked for Supreme Court Justice Sherman Minton, served in the U.S. Army, and moved to New York’s Upper East Side in 1956 to join Cravath, Swaine & Moore, the white-shoe law firm where he would spend over half a century. Talk about loyalty.

He made partner in 1960, and two decades later became Presiding Partner—a role he held until 1999, the firm’s second-longest tenure after its founder, Paul Cravath. His clients included Disney, CBS, Westinghouse, and GEICO. One of his favorite relationships was with Warren Buffett, a fellow Midwesterner who also enjoyed a good boardroom.

The first time I met Sam was at Lusardi’s, a cozy Italian spot on Second Avenue and 78th St. He and Sally kept a standing Sunday night reservation, and any of their three children or adult grandchildren were welcome to show up for a meal. I was nervous the first time Nick invited me to join. I’d built my career in the style world, writing about art openings and fashion trends. What on earth was I going to talk about with Warren Buffett’s lawyer?

Didn’t matter. Sam was endlessly curious—about me, about going from Missouri to Manhattan, about what really happens at fashion shows. (Could he come to one?) He asked how contemporary art had gotten so expensive and if the paintings of clown faces in his library were worth anything. (Funnily enough, no.) He humored my law questions and was happy to chat about musicals, gardening, Thanksgiving menus, all of New York’s great institutions. He devoured newspapers, biographies, magazines. He never sat still without something to read—even while Sally drove.

I knew I made it when he added me to the family email thread. By Thanksgiving, I was in Connecticut peeling potatoes. I’d borrowed a grandfather, at last.

Nick has told the story about how, when he came out as a gay man, like most of us, there was a sense of foreboding, maybe even fear. One day, he received a call from Sam, which was a surprise. Sam believed phone calls without warning were reserved for emergencies. (I wholeheartedly agree with this, for the record.) Sam asked if he was alone, and then he told him:

“You deserve every opportunity and privilege in life. Promise me you will build a family and be a father.”

Sam excelled in a deeply heteronormative world—Military school! Football! Boardrooms! Finance bros! Yet, Nick says this didn’t feel like a hard call for Sam to make. He knew where Nick was and what he needed to hear.

It’s not an exaggeration to say this one phone call set the course for everything that followed—for Nick, for me, for our children. It nudged us toward the life we now have, a life beyond anything I could have imagined growing up in the Midwest. Grandpa Sam had a rare gift of being both deeply direct and emotionally subtle. For him, family had no shapes or colors or exclusionary programming. Family was family.

After he died, The New York Times obituary described the type of lawyer Sam prided himself on being: “I do not regard myself as a classic M&A transactional lawyer. I would regard myself as a relationship lawyer.” That's who he was. In law and in life. A relationship man.

Warren Buffett, who met Sam in the mid-1970s, remembered him with great admiration. He has said that when Sam was in charge, he could have added his name to the Cravath, Swaine & Moore masthead—but wasn’t interested. According to Buffett, that wasn’t who Sam was. He didn’t care about titles or prestige; he cared about doing right—by his clients, his colleagues, his community.

Buffett’s office also noted that when Sam started at Cravath, the average closing price of the DJIA (Dow Jones Industrial Average—don’t worry, I had to look that up too) was $963.99. When he stepped down, it was $8,629.91. “Sam was a remarkable friend and a remarkable lawyer,” he told The New York Times.

Last Monday, Sam’s friends, family, and business associates gathered at the New York Public Library, where he served as a board member for 45 years and chairman from 1999 to 2004. The Celeste Bartos Forum was cool, dark, and, instead of flowers, the stage was decorated with magnolia, rhododendron, and other greenery native to Indiana. Behind it all was a sepia mural of New York’s East Side, seen from the Central Park reservoir.

The memorial was scheduled for 11 a.m., but at 10:59, half the seats were empty. I squirmed—Sam deserved nothing less than a packed house. Then the music started, and more than 100 Cravath partners, past and present, filed into the room in a solemn procession, filling every single empty seat. It was a stunning entrance—one I was told later Sam had begun organizing years earlier for partners’ funerals. It really got me.

Faiza Saeed, Cravath’s current presiding partner and the first woman to lead the firm in its 200-year history, recalled working on some of Buffett’s deals. She remembered how Sam made room for her at the table—literally and figuratively. Paul LeClere, the Library's President Emeritus, said, “Sam became a lawyer because he wanted to do what was right, not what would win.”

The service was filled with music from his favorite musicals, including Oklahoma, The King and I, and Anything Goes. They played “You’re the Top.” Sam’s favorite holiday was Christmas, so we heard “We Need a Little Christmas” from Mame. The final song was “Seventy-Six Trombones” from The Music Man, and Sam’s children marched down the aisle playing air trombones like they did decades before.

After the service, his final wish was honored: a towering chocolate cake—‘Jabba the Cake’—was wheeled out, inspired by his beloved Hershey’s Kisses. The recipe? Boxed cake mix and hand-whipped fudge icing. Nothing fancy. Just perfect.

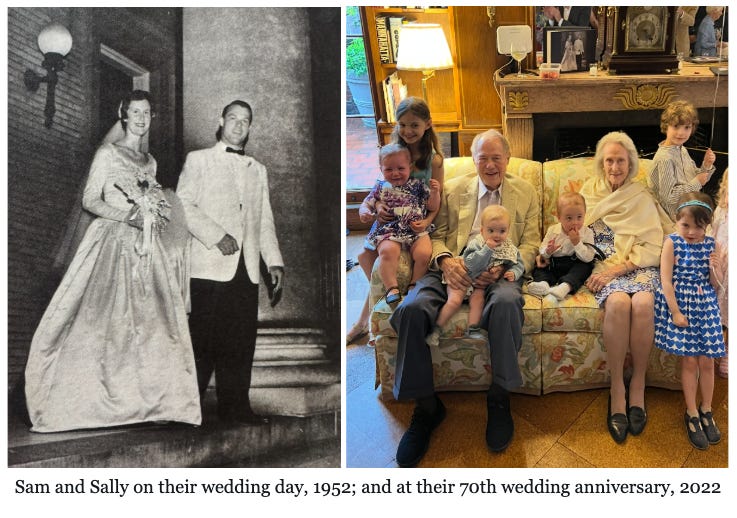

I’ve spent the past week scrolling through photos. There’s one of me trying to impress Sam with a green thumb in his Connecticut garden. (Turns out I’m a better griller than I am a farmer.) There’s one from Sam and Sally’s 90th birthday in 2020, when Nick showed up in a COVID mask with a chocolate cake and set up a family Zoom. There’s one of Sam at Nick’s sister’s wedding, beaming with Sally on his arm. There’s a seriously stylish one we took when we surprised him at the old Cravath offices in summer 2018. We found him in a seersucker suit, naturally, looking like a matinee idol.

More recently, there are pictures of Grace and Noah meeting their great-grandparents for the first time—two joyful, chubby little blobs bouncing on laps in a home where four generations of Butlers had gathered to break bread and share love. After Sally passed, we’d bring the kids up to see Sam every weekend to lift his spirits; they’d sit with him, reading books and playing with his hippo figurines—small, gentle reminders of his presence that still live in their hearts.

There are pictures of the kids’ final visit with Sam last winter. As we said goodbye, Grace gave him a hug, held up her stuffed hippo, and asked, “Do you want to sleep with him tonight?”

I’m deeply grateful to Sam’s children and grandchildren for letting me feel like part of the family. Being a part of his world was a constant source of inspiration and amusement, a gift of a grandfather.

Sam was truly one of a kind: a man who lived with quiet strength, boundless kindness, and a heart that made his whole family feel seen. He was the kind of man we wish this country produced more often—the small town boy who moves to the big city and fulfills the American Dream.

Now, whenever I hear the opening lines of Oklahoma!, I think of Sam, and how, no matter the storm, he carried that beautiful feeling with him every morning:

“Oh, what a beautiful mornin’, / Oh, what a beautiful day.

I got a beautiful feelin’ / Ev'erything’s goin’ my way.”

“As we said goodbye, Grace gave him a hug, held up her stuffed hippo, and asked, “Do you want to sleep with him tonight?” 🤍🤍🤍

Well done! Very moving and so lovely!